The Sekenesse of Wymmen

'Because there are many women who have numerous diverse illnesses – some of them almost fatal – and because they are also ashamed to reveal and tell their distress to any man, I therefore shall write somewhat to cure their illnesses, praying to merciful God to send me grace to write truly to His satisfaction and to the assistance of all women.'

So begins Beryl Rowland's translation of the text in Middle English dealing with 'The Sekenesse of Wymmen', written in the 15th century and found in British Library Sloane MS 2463.

It looks as if we have found a gynaecological text addressed to women (as Rowland thought), presumably written in English rather than Latin to help them read it, and meant to be used by women – but appearances are deceptive. For one thing the first known owner of this manuscript was a man, Richard Ferris, sergeant surgeon to Queen Elizabeth I and master of the Barber-Surgeon's Company, who may have added his own glosses to the text. When he died, it passed to another man, John Felde, an astrologer and associate of the magus John Dee.

As Monica Green has proved, the later in the Middle Ages you look, the more you find that men have taken over the knowledge of women's bodies, making gynaecology masculine. The idea that women's diseases were women's business, and that women were 'ashamed to reveal and tell their distress to any man', as this text has it, does not actually correspond to what we know about medical practice in the 15th century. An English medical practitioner like Thomas Fayreford, working in the west country at about the same date this manuscript was made, seems to have treated more cases of 'suffocation of the womb' than any other disease; even Franciscan and Dominican friars seem to have treated women's diseases.

'The Sekenesse of Wymmen' turns out to be largely made up of a translation of chapters on women's diseases in the Latin book called the Compendium medicinae of Gilbertus Anglicus, written as a treatise on practical medicine around 1240 CE. So the author of this text was male too, but happy to write on gynaecology and obstetrics. Gilbertus himself was drawing on the earlier Practica medicinae of Roger de Barone. There is other additional material too in 'The Sekenesse of Wymmen' that is not in Roger or Gilbertus. The only bits that have anything to do with a woman as author are the chapters on ano-vaginal fistulas and uterine prolapse, which are translated from the corpus of three Latin texts called collectively the Trotula, because of their association with a famous female doctor, Trota of Salerno.

The rest of Sloane MS 2463 contains some pretty technical texts on surgery, as well as a collection of recipes. Since 'The Sekenesse of Wymmen' was not a separate fascicle in this manuscript, but seems to have been written at the same time and by the same scribes as the rest, it is likely to have shared the readership of male practitioners with an interest in surgery rather than to have circulated amongst women. There is the possibility that some sections of the text, especially the obstetrical material, may have been read out or otherwise passed on to midwives, but they are not likely to have been the primary readers or owners. Interestingly the text occasionally refers to contemporary practice by both men and women: for example in one case, 'probatum est in Chepa London' (p.464, Green and Mooney 2006).

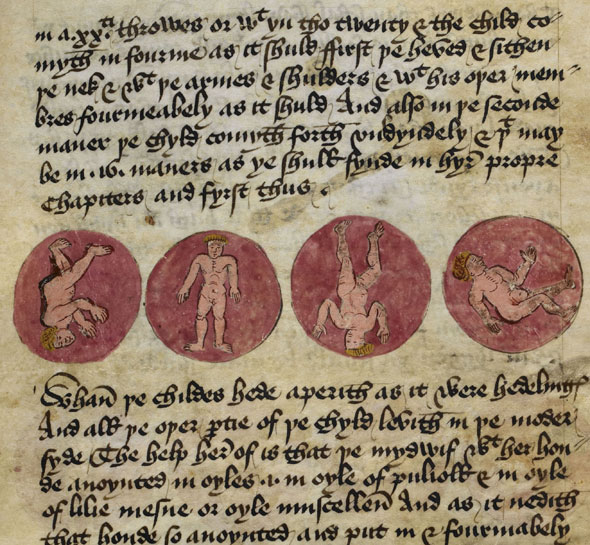

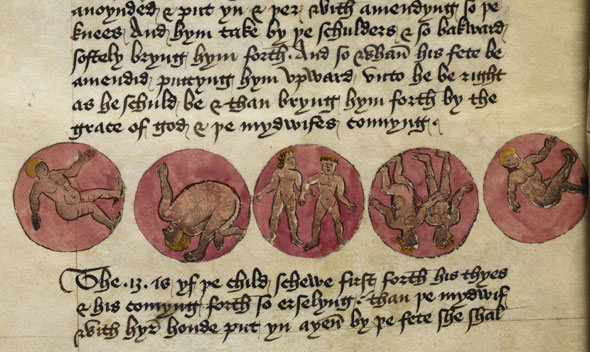

I was first attracted to this manuscript and 'The Sekenesse of Wymmen' by the illustrations, a series of 17 figures of a child or children in red circles representing the womb. These pictures are not at all realistic. Any sign of an exit from the womb is missing, and the children are little 'homunculi', nothing like foetuses. All of the series appear to deal with unnatural presentation of the child at birth, and the accompanying brief instructions inform the reader that the chief duty of the birth attendant in the case of a child presenting unnaturally is to push the child back into the vagina and try to rearrange it.

It seems that this series of images only came to be attached to the text 'The Sekenesse of Wymmen' as one late stage in a long and varied career. The series may go right back to late antique times, more than a thousand years before their appearance in Sloane MS 2463. They are found earlier in the Middle Ages in a 9th century manuscript of the Gynaecia of Muscio, which was a modified Latin translation of the gynaecological writings of the 2nd century Greek physician Soranus of Ephesus. The brief instructions on malpresentations in our text, as well as the pictures, seem to derive from Muscio.

Nor did the peripatetic career of these pictures stop in the 15th century. The same series appeared in printed books, for example as images printed from woodblocks in Eucharius Roesslin's Der Swangern Frauen und Hebammen Rosegarten, which appeared at Strasburg and Hagenau in 1513. Roesslin's work claimed to be directed at midwives, unlike our manuscript, though it seems that it too was also used by physicians and laymen. It is doubtful though whether any user of these texts, professional or lay, would have found the illustrations very helpful.

Knowledge of what to do in childbirth was probably in any case more a matter of oral communication between women in the 15th century, than a matter of knowledge passed on by reading and writing. Once women began the process in lying-in for birth they were confined to a bedroom and their attendants and 'gossips' were all female. It was normal, at least in aristocratic households, to seal off the room physically from males, even to stop the keyholes to preserve female secrets. Women were present at birth to help the mother and child but also to bear witness later so that there should be no question about the legitimacy of inheritance (should the child be male).

Peter Jones (King's College, Cambridge)

Further reading

Monica H. Green, 'Obstretrical and Gynecological Texts in Middle English', Studies in the Age of Chaucer 14 (1992), 53–88

Monica H. Green and Linne Mooney, 'The Sickness of Women', in M. Teresa Tavormina (ed.), Sex, Aging and Death in a Medieval Medical Compendium: Trinity College Cambridge MS R.14.52, its texts, language, and scribe, 2 vols., II, 455–568 (Tempe, AZ: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2006)

Monica H. Green, Making Women's Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008)

Monica H. Green, 'The Sources of Eucharius Roesslin's "Rosegarden for Pregnant Women and Midwives" (1513)', Medical History 53 (2009), 167–92

Peter Murray Jones, Medieval Medicine in Illuminated Manuscripts (London: British Library, 1998)

Beryl Rowland, Medieval Woman's Guide to Health (London: Croom Helm, 1981)